Ancient Times

Writings on salt no doubt also existed on the clay tablets of Ancient Babylon and on Egyptian papyri. Even without written evidence we can be fairly certain that salt-making and use was a feature of life in all ancient communities. Where isolated from modern trade and technology, some still today make salt by the same prehistoric methods.

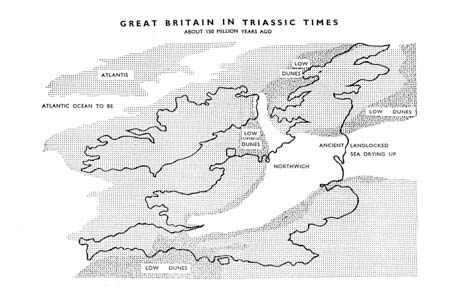

In the British Isles, prehistoric man will have made his salt from sea water or from the few places where inland brine springs had been discovered. Traces of these activities are difficult to identify but archaeological evidence is now reaching back into the Bronze Age.

Cheshire was on a Neolithic trade route which crossed the salt fields where Iron-Age Britons probably traded Westmoreland stone axe-heads for salt.

More Salt History:

- Salt During Our Early History (inc Ancient, Iron Age, Roman & Anglo Saxon Times)

- Salt in the Middle Ages (inc Normans, Late Medieval, the Black Death, Tudor & Stuart Periods)

- Early Modern Period (Technology & Change)

- Salt & the Chemical Revolution

The Iron Age

Archaeological evidence of Iron Age salt-making in Britain has been largely based on the discovery of remnants of coarse pottery vessels and supporting pillars recognised as being connected with salt-making and known as briquetage.

Sea water or brine from inland springs was evaporated in these vessels over fires to give a residual lump of salt.

There have been extensive finds of Iron Age briquetage in the Lincolnshire and East Anglia Fenlands and along the Essex coastline. Here the sea water was concentrated in pottery pans 60cm wide, 120cm long, and about 12mm thick.

The strong brine was then evaporated in small pottery vessels supported on pillars to give the lump of salt which was obtained by breaking the vessels.

Archaeological digs at salt-making sites in Cheshire and Worcestershire have produced relatively small amounts of briquetage when compared with the coastal sites.

It appears that the finished salt was distributed in the characteristic coarse pottery vessels in which it was made. The briquetage from these vessels has thus been discovered at Iron Age settlements over a wide area of Wales and western England.

Clay dug between Middlewich and Nantwich has been shown to have been used to make the pottery fragments found at these Iron Age sites.

Archaeologists have also found evidence of iron-age salt-making in the area between Middlewich and Nantwich. At Middlewich (Salinae) excavations have revealed brine kilns on which Iron Age type earthenware vessels of brine were heated.

Roman Times

In Britain, lead salt pans were used by the Romans at Middlewich, Nantwich and Northwich and excavations at Middlewich and Nantwich have revealed extensive salt-making settlements.

Roman soldiers were partly paid in salt. It is said to be from this that we get the word soldier – ‘sal dare’, meaning to give salt. From the same source we get the word salary, ‘salarium’.

Salt was a scarce and expensive commodity and its value was legendary. To sit above or below the salt identified precedence in the seating arrangements at a feast, according to one’s rank. Not to be worth one’s salt was a great insult. The Bible compliments some men as being ‘the salt of the earth’.

At the time of the Roman Conquest, British salt making had been long established at numerous coastal sites and at the inland brine springs of Cheshire and Worcestershire.

Salt was a vital commodity to the Roman army and this demand will have been met by establishing military salt works. At the inland sites the nearly saturated natural brine would require much less fuel and time to make salt than from the evaporation of weakly saline sea water.

Middlewich

The Roman army’s advance to the North reached Cheshire by around 60AD and established military bases at Chester and Middlewich.

Chester was a supply port and a convenient military base from which to gain control of North Wales with its lead and silver mines. At Middlewich a fort was built on a defensive site above the River Dane and this became a staging post on the main military road to the North.

At Middlewich the Romans established their saltworks on land by the River Croco between the military fort and the site of the existing Celtic salt making settlement.

At both Middlewich and Nantwich digs have produced a wealth of Roman period finds such as leatherwork, pottery and timber-lined, clay-packed pits. But both sites appear to lack the mass of briquetage which has been a feature of other salt making sites and indicative of Iron Age/ Bronze Age occupation.

Middlewich has produced some briquetage indicative of early salt making but the Nantwich 2002 dig appears to have been a Roman lead pan site without earlier or later occupation. But no evidence remained of supporting substructures for the pans.

Lead Salt Pans

The Romans were the first to use lead salt pans to evaporate brine and produce salt. The pans used by the Romans were typically about 90-100cm square by 15cm deep. Excavations have yielded a number of such pans and we even know the names of a few of the Roman saltmakers thanks to inscriptions on some of the lead pans – Viventius, Veluvius and Cunitus. One pan is inscribed “COPI” which could mean it belonged to a Christian bishop – placing this pan in the late Roman period.

Complete Roman salt pans are in the Salt Museum and at the Nantwich Museum. The pan on display at the Salt Museum in Northwich is one of the four found at Northwich in 1864. The Lion Salt Works has three medieval pans found at Bostock near Middlewich in 1986 and also a replica Roman size lead pan which is used for live salt boiling displays.

Lead salt pans were to be used continuously in Cheshire for fifteen centuries and were only replaced with iron pans in the 17th century when economic conditions made it necessary to change from a wood fuel to the much hotter burning coal. Documentary sources record the use of many hundred lead pans at the Cheshire salt towns during the late medieval period.

Medieval pans are without inscription and rectangular. They are also slightly smaller than the Roman pans at about 90cm by 60cm and 13-15 cm deep. Documents of the 16th/17th century tell us the size of the lead pans then in use. Shortly after the Norman conquest, salt pans grew larger. By the 14th century pans, made from sheets of cast lead beaten up at the sides, measured about 170cm x 90cm.

Brine evaporation occurs with the deposit of scale on the hot pan bottom where this is exposed to the fire beneath. If this is allowed to become too thick the lead will overheat and melt. Hence the scale was regularly removed by picking with an iron implement which has left a pick mark on the lead bottom. All the Roman pans show these pick marks as a band down the middle with pick-free zones on either side. This shows that the pans were supported on solid walls about 50cm apart but surprisingly we have been left with no conclusive archaeological evidence of the nature of these substructures.

Lead melts easily and pans would regularly be damaged by overheating. However, it is a readily recyclable metal and the lead from an damaged or unusable salt pan would be melted down and made into a new pan or put to other use.

Anglo Saxon

There has been continuous salt production on the same sites at Droitwich from the Iron Age through the Roman and Medieval periods, and up to the 20th century.

However, in Cheshire, recent archaeology at both Nantwich and Middlewich has confirmed that the Romans established new salt works on green field sites which were then abandoned and returned to agriculture.

This was either with their departure in the 5th century or possibly even during the occupation.

One explanation is that these were Roman Army saltworks, providing salt for their own needs, while Romano-British salt makers occupied long established Celtic salt making sites nearby and continued to supply the traditional needs of the local population and the itinerant traders who travelled into Wales and to the North.

These long established sites were in time to become the medieval ‘wiches’.

Salt Making & The Domesday Book

Salt making continued in post Roman Cheshire, at first through a period of Welsh control and then as part of the Anglo-Saxon Mercia. The same pattern of trade will have continued and later this attracted Viking influence from the North. The first documentary account of Anglo-Saxon salt making in Cheshire is found in the Domesday Book of 1086.

In 1086 the salt industry at the Cheshire “Wiches” was slowly recovering from the laying waste by William after the rebellion of 1070. However, the task of the Domesday commissioners was to assess potential worth and they made use of what could have been an existing documentary record of the fiscal control of salt making and distribution “in the time of King Edward”. This describes what must have been a long established industry developed during several centuries of Anglo-Saxon rule and could have retained elements of Roman control. There was little if any change in the technology during this period.

Domesday also reveals one other secret of Anglo Saxon saltmaking. We learn that there was a salthouse in the manor of Burwardestone, now lost, but thought to be the manor of Iscoyd in Maelor Saiseg, the detached part of Wales. In 1086 it was held by Robert Fitzhugh but was claimed by the Bishop and according to the 1094 Foundation Charter of St Werbergs, Robert gave back the saltworks to the Abbey and it was then known as Fulwich —a fourth Cheshire “wich”.

At Droitwich the Commissioners produced a conventional entry in the Worcester Domesday. The town and its salt making had not been “laid waste” and had presumably continued unchanged since before 1066.

Coastal Salt Making

Domesday also records those manors which owned coastal salt making sites (salinae or salterns) along the coast between Lincolnshire and Cornwall. Quoted estimates of the number of such manors are between about 300 and 1195 but, whatever the number, it was considerable.

The main concentrations were in the Lincolnshire- East Anglian fenlands and along the South coast.

Coastal salt-making in England took what advantage it could of solar evaporation and tended to be seasonal. But the final stage to give dry salt always involved evaporating the brine over a fire, at first in ceramic vessels and later in lead pans.

As a result of Fenland drainage many of these sites are now several miles inland and have been the subject of extensive archaeology.